Miles Bair's paintings have a way of harmonizing contrasts: contrasts between depth and flatness, contrasts between borders and the images the borders enclose, contrasts between brilliance and shadow (especially in the paintings with gold), and most importantly, contrasts between realistic representations of the natural world and the abstraction of the dots and geometric shapes that comprise them.

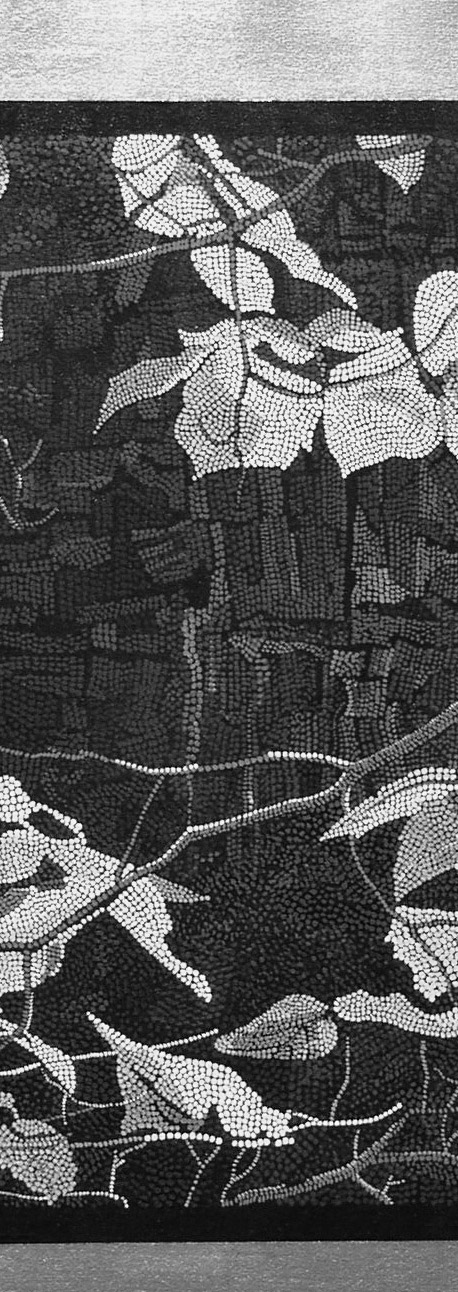

The cumulative effect of these harmonized contrasts is to provide a sense of profound stillness. On first glance it seems as if the source of this sense of stillness is the beauty and tranquility of the landscape, and to be sure, these things are important. But shifting one's perspective on the paintings tells a different story. The technique of clustering dots and other abstract shapes to form images makes seeing the paintings close up a very different experience from seeing the same paintings from a distance, and to move back and back and forth between the two views is to become aware of the importance of perception to our experience not just of the painting but of the natural world. The stillness of a Miles Bair painting is ultimately not the stillness of nature but the stillness of the zen-like mental state required to let go of the noise and disturbance of everyday life and to be fully present for and alive to nature's apprehension by the senses and the spirit.

Wes Chapman

Wes Chapman is an Associate Professor of English and Chair of the English Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. He is the author of"Cyborg Imagination in the Age of Digital Incunabula" and Turning In.

(From the publication, Miles Bair: Painting.)

———————————————————————————————-

In the woods there are moments when it seems as if something momentous is about to take place, building, gaining momentum, gathering all together. Miles Bair’s paintings capture those satori-like moments when the world reveals itself to us: the quicksilver flute-song of the thrush hidden deep, the bright clarity of a dawn sky, the call of the jay from tree to tree, the fall of dark water over mossy rocks, the dignity of crabbed and ancient pines beneath their thick and shining layer of snow, the illuminating suffusion of a golden dusk.

Meanwhile, his characteristic pointillist technique calls our attention to the ways in which we apprehend nature: each time we come near, views resolve and dissolve, form and reform. To view one of Miles Bair’s paintings is to understand what it is to see the world and one’s place in it anew—every time.

Alison Sainsbury

Alison Sainsbury is an Emerita Professor of English at Illinois Wesleyan University and the author of Lost River and "Another Story from Bear Country". (From the publication, Miles Bair: Paintings.)

———————————————————————————————

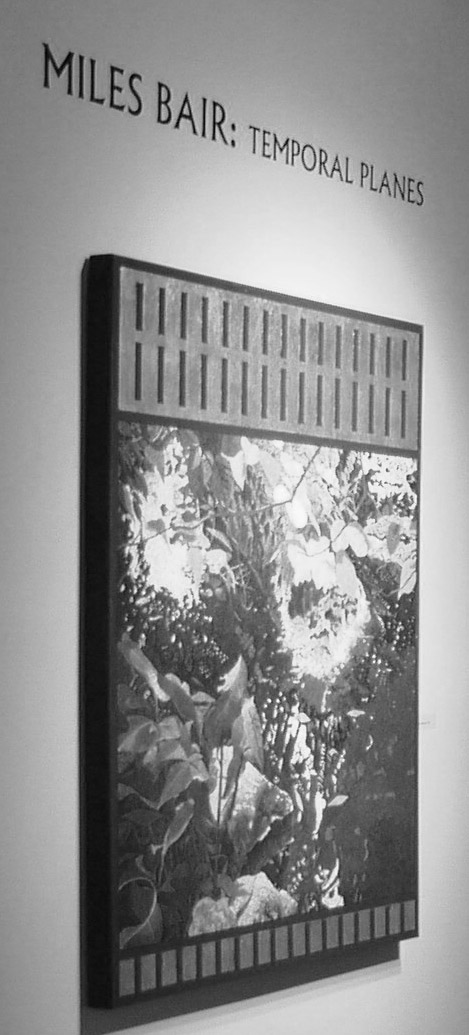

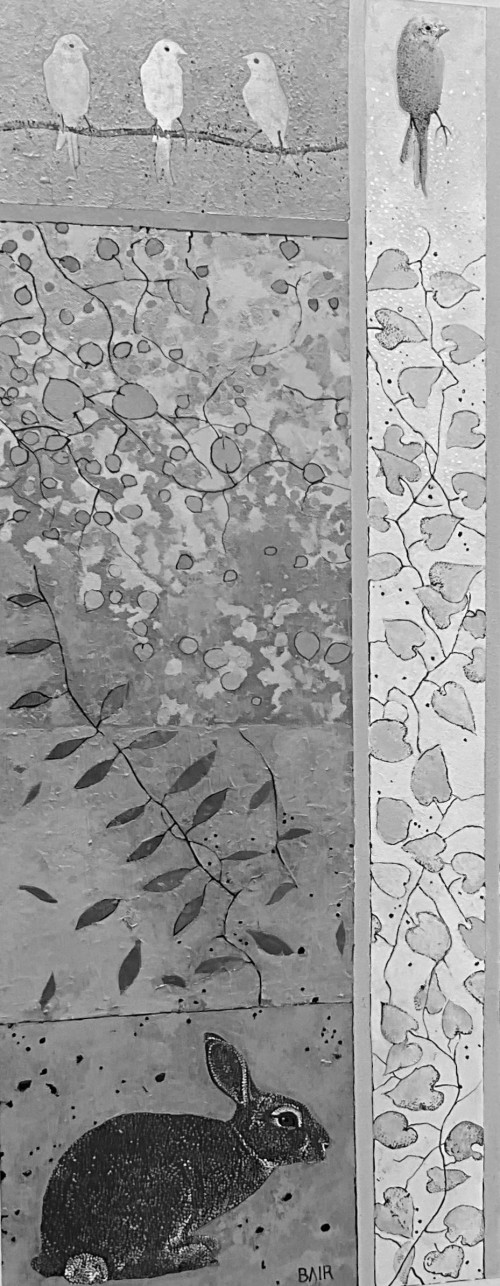

Miles Bair’s recent works are the latest in the artist’s long preoccupation with matters of how we consider nature through and within the frameworks provided by multiple forms of cultural edifice. Styles and imagery derived from and inspired by multiple sources rub against one another as areas of Bair’s paintings literally frame, corral, crop, anchor, obscure, and reveal one another, resulting in a kind of endless cultural relativity surrounding nature and landscape. Romantic and astute, Bair’s works are sly with regard to their multiple engagements of culture(s)—eschewing familiar critiques of the mediation of nature, and instead embracing mediation as a starting point for works as evocative as they are quietly provocative.

Christopher Miles

Christopher Miles is a Professor of Art Theory and Criticism at California State University, Long Beach and presently writes for Artforum, Art in America, Flash Art, Flaunt, Frieze and The Los Angeles Times.

(From the catalog essay, "Bloomington")

——————————————————————————————-

It was with awe

That I beheld

Fresh leaves, green leaves,

Bright in the sun.

Basho (Japanese 1644-1694)

Translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa

Like Japanese haiku, these paintings by Miles Bair employ a deceptively simple structure to capture the ethereal beauty of natural spaces and convey complex feelings of wonder and solitude.

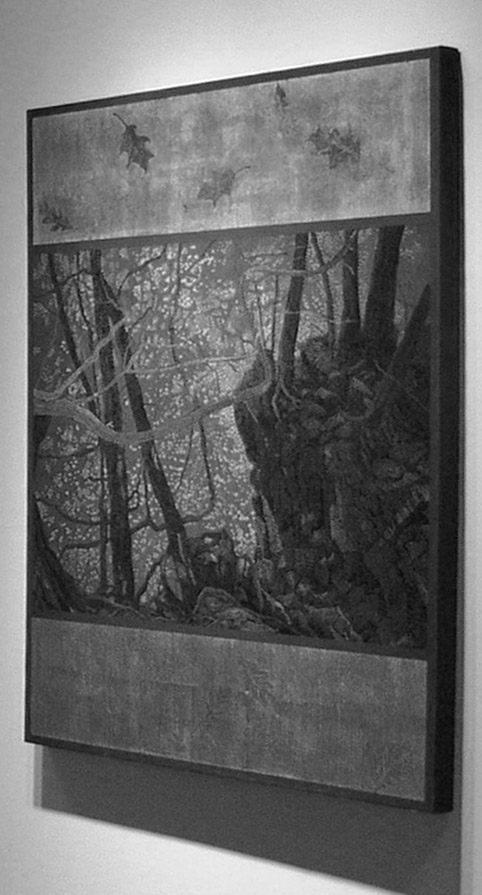

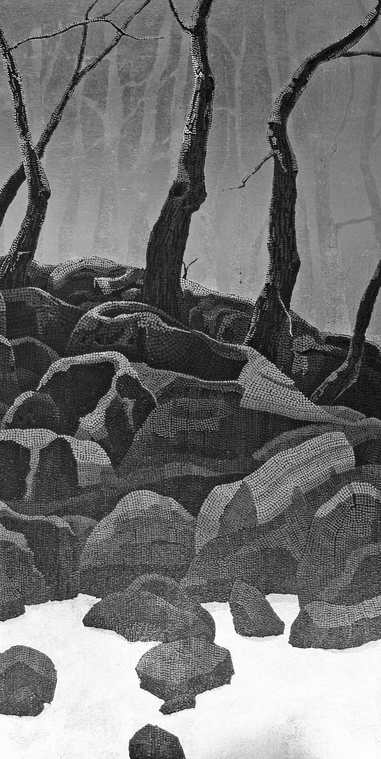

Combining his commitment to art making with an intense interest in Japanese aesthetics, Miles Bair explores all that the painting medium allows. Bair first applies two to three coats of black gesso to the stretched canvas, then using white chalk traces compositions derived from photographs, memory, and invention. Using his dot pattern technique, the landscape compositions emerge from a structured yet abstract application of paint. Bair heightens and resolves the color by layering glazes in the same manner. Further Bair offers, with the Japanese-influenced areas of gilded gold and silver, an architectural and decorative sensibility to the paintings. These areas and the landscape compositions work in tandem to capture the ethereal beauty of natural spaces and elicit a sensual response.

Like scenes in a Japanese folding screen, the scale in Bair’s paintings is often ambiguous. Instead of gazing into a receding distance the eye is taken on a journey. Scanning from side to side and top to bottom, the eye is confronted with trees and rocks, leaves and water, and occasionally birds and fish. As the eye journeys, so the mind confronted for instance by the sadness of autumn leaves floating down a stream reflects on the transience of human life.

Obviously the landscape is a major component of these paintings and reflects the artist’s response to specific places: Bair grew up in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains, lives in wooded area of central Illinois, spends quality time in the north woods of Wisconsin, and travels often to Japan to conduct research. Yet with ease and inventiveness, Bair’s compositions range from the real to imagined. The trees may or may not be identifiable. The leaves stylized in a border may or may not relate to the trees depicted in the landscape portion of the painting; they may actually be tracings of real leaves from Bair’s yard or a direct reference to a Japanese screen painting. The truth Bair follows is being true to what each individual painting requires.

The stylistic and formal techniques used in the paintings allow Bair liberal expression. Like other American artists who pay homage to an ancient cultural form while making their own individual statement, Bair communicates through these works a wonder of the natural world and our ultimate connection to it. The poetic and quiet beauty of his paintings fittingly corresponds to poems written with apparent simplicity and oriental balance by Robert Bly.

The strong leaves of the box-elder tree,

Plunging in the wind, call us to disappear

Into the wilds of the universe,

Where we shall sit at the foot of a plant,

And live forever, like the dust.

Robert Bly (American, 1926- )

Poem in Three Parts, III, from Silence in the Snowy Fields, 1962

Alison Hatcher, MCAC Curator (from a 2005 catalog essay)

——————————————————————————————

Any landscape is composed of not only what lies before our eyes but what lies within our heads. Donald W Meinig

The landscape paintings of Miles Bair are derived from specific locations, but, as Bair states, many of the images I paint are invented or they come from memory. ...Sometimes I combine natural features from various places--a stream from one location and trees from another. I sketch and photograph, but mostly I remember. And, like fleeting memories, Bair's paintings capture almost dreamlike images that flow between what is real and what is imagined.

Marilyn F. Stasiak, Curator of Art

( from Miles Bair: The Fleeting Landscape, Neville Public Museum

Publication, 2011)

The cumulative effect of these harmonized contrasts is to provide a sense of profound stillness. On first glance it seems as if the source of this sense of stillness is the beauty and tranquility of the landscape, and to be sure, these things are important. But shifting one's perspective on the paintings tells a different story. The technique of clustering dots and other abstract shapes to form images makes seeing the paintings close up a very different experience from seeing the same paintings from a distance, and to move back and back and forth between the two views is to become aware of the importance of perception to our experience not just of the painting but of the natural world. The stillness of a Miles Bair painting is ultimately not the stillness of nature but the stillness of the zen-like mental state required to let go of the noise and disturbance of everyday life and to be fully present for and alive to nature's apprehension by the senses and the spirit.

Wes Chapman

Wes Chapman is an Associate Professor of English and Chair of the English Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. He is the author of"Cyborg Imagination in the Age of Digital Incunabula" and Turning In.

(From the publication, Miles Bair: Painting.)

———————————————————————————————-

In the woods there are moments when it seems as if something momentous is about to take place, building, gaining momentum, gathering all together. Miles Bair’s paintings capture those satori-like moments when the world reveals itself to us: the quicksilver flute-song of the thrush hidden deep, the bright clarity of a dawn sky, the call of the jay from tree to tree, the fall of dark water over mossy rocks, the dignity of crabbed and ancient pines beneath their thick and shining layer of snow, the illuminating suffusion of a golden dusk.

Meanwhile, his characteristic pointillist technique calls our attention to the ways in which we apprehend nature: each time we come near, views resolve and dissolve, form and reform. To view one of Miles Bair’s paintings is to understand what it is to see the world and one’s place in it anew—every time.

Alison Sainsbury

Alison Sainsbury is an Emerita Professor of English at Illinois Wesleyan University and the author of Lost River and "Another Story from Bear Country". (From the publication, Miles Bair: Paintings.)

———————————————————————————————

Miles Bair’s recent works are the latest in the artist’s long preoccupation with matters of how we consider nature through and within the frameworks provided by multiple forms of cultural edifice. Styles and imagery derived from and inspired by multiple sources rub against one another as areas of Bair’s paintings literally frame, corral, crop, anchor, obscure, and reveal one another, resulting in a kind of endless cultural relativity surrounding nature and landscape. Romantic and astute, Bair’s works are sly with regard to their multiple engagements of culture(s)—eschewing familiar critiques of the mediation of nature, and instead embracing mediation as a starting point for works as evocative as they are quietly provocative.

Christopher Miles

Christopher Miles is a Professor of Art Theory and Criticism at California State University, Long Beach and presently writes for Artforum, Art in America, Flash Art, Flaunt, Frieze and The Los Angeles Times.

(From the catalog essay, "Bloomington")

——————————————————————————————-

It was with awe

That I beheld

Fresh leaves, green leaves,

Bright in the sun.

Basho (Japanese 1644-1694)

Translated by Nobuyuki Yuasa

Like Japanese haiku, these paintings by Miles Bair employ a deceptively simple structure to capture the ethereal beauty of natural spaces and convey complex feelings of wonder and solitude.

Combining his commitment to art making with an intense interest in Japanese aesthetics, Miles Bair explores all that the painting medium allows. Bair first applies two to three coats of black gesso to the stretched canvas, then using white chalk traces compositions derived from photographs, memory, and invention. Using his dot pattern technique, the landscape compositions emerge from a structured yet abstract application of paint. Bair heightens and resolves the color by layering glazes in the same manner. Further Bair offers, with the Japanese-influenced areas of gilded gold and silver, an architectural and decorative sensibility to the paintings. These areas and the landscape compositions work in tandem to capture the ethereal beauty of natural spaces and elicit a sensual response.

Like scenes in a Japanese folding screen, the scale in Bair’s paintings is often ambiguous. Instead of gazing into a receding distance the eye is taken on a journey. Scanning from side to side and top to bottom, the eye is confronted with trees and rocks, leaves and water, and occasionally birds and fish. As the eye journeys, so the mind confronted for instance by the sadness of autumn leaves floating down a stream reflects on the transience of human life.

Obviously the landscape is a major component of these paintings and reflects the artist’s response to specific places: Bair grew up in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains, lives in wooded area of central Illinois, spends quality time in the north woods of Wisconsin, and travels often to Japan to conduct research. Yet with ease and inventiveness, Bair’s compositions range from the real to imagined. The trees may or may not be identifiable. The leaves stylized in a border may or may not relate to the trees depicted in the landscape portion of the painting; they may actually be tracings of real leaves from Bair’s yard or a direct reference to a Japanese screen painting. The truth Bair follows is being true to what each individual painting requires.

The stylistic and formal techniques used in the paintings allow Bair liberal expression. Like other American artists who pay homage to an ancient cultural form while making their own individual statement, Bair communicates through these works a wonder of the natural world and our ultimate connection to it. The poetic and quiet beauty of his paintings fittingly corresponds to poems written with apparent simplicity and oriental balance by Robert Bly.

The strong leaves of the box-elder tree,

Plunging in the wind, call us to disappear

Into the wilds of the universe,

Where we shall sit at the foot of a plant,

And live forever, like the dust.

Robert Bly (American, 1926- )

Poem in Three Parts, III, from Silence in the Snowy Fields, 1962

Alison Hatcher, MCAC Curator (from a 2005 catalog essay)

——————————————————————————————

Any landscape is composed of not only what lies before our eyes but what lies within our heads. Donald W Meinig

The landscape paintings of Miles Bair are derived from specific locations, but, as Bair states, many of the images I paint are invented or they come from memory. ...Sometimes I combine natural features from various places--a stream from one location and trees from another. I sketch and photograph, but mostly I remember. And, like fleeting memories, Bair's paintings capture almost dreamlike images that flow between what is real and what is imagined.

Marilyn F. Stasiak, Curator of Art

( from Miles Bair: The Fleeting Landscape, Neville Public Museum

Publication, 2011)